Autoinflammatory diseases are conditions in which the innate immune system, for unknown reasons, becomes activated and triggers inflammation. The innate immune system is the body’s rapid first line of defense against infection. The heat, swelling, and redness of inflammation are a normal part of the body’s protective response to injury or infection. However, prolonged inflammation can seriously damage the body.

In 2004, Dr. Raphaela Goldbach-Mansky of NIH’s National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) examined a 10-year-old girl who had signs of systemic inflammation, especially in the blood vessels. The girl hadn’t responded to any medications her doctors had tried. She had blistering rashes on her fingers, toes, ears, nose, and cheeks, and she’d lost parts of her fingers to the disease. She also had severe scarring in her lungs and was having trouble breathing. Signs of her disease had appeared in infancy and progressively worsened. She died a few years later.

After seeing 2 other patients with the same symptoms, Goldbach-Mansky’s team suspected that all 3 had the same disease, and that it might be caused by a genetic defect that arose in the children themselves, rather than being inherited. The scientists, including co-lead authors Drs. Yin Liu, Adriana A. Jesus, and Bernadette Marrero, investigated the genetic basis of the syndrome. They began by sequencing the whole exomes (protein-coding regions of DNA) of the first patient and her parents. The study appeared online on July 16, 2014, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The team identified a mutation in a candidate gene, TMEM173, that was carried by the girl but not her parents. TMEM173 encodes a protein called stimulator of interferon genes (STING). STING is part of a pathway that recognizes foreign DNA—such as that from viruses and bacteria—and signals cells to produce interferons, which stimulate the innate immune system.

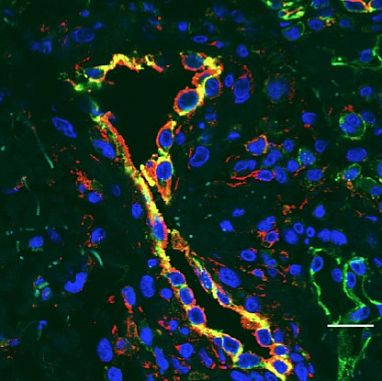

Sequencing the gene in 5 unrelated children with similar symptoms revealed a total of 3 STING mutations in the patients that weren’t in any of their parents. The scientists found that these mutations boosted STING activity. In addition, STING is expressed in the cells lining the blood vessels and the lungs, which would likely explain why these tissues are predominantly affected by the disease. The team named the disease STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy (SAVI).

The scientists tested 3 drugs that belong to a new class called JAK inhibitors (tofacitinib, ruxolitinib, and baricitinib). These drugs inhibit the interferon pathway. All 3 inhibitors blocked the effects of the mutations on patient cell samples in the laboratory.

“Blood tests on the affected children had shown high levels of interferon-induced proteins,” Goldbach-Mansky notes, “so we were not surprised when the mutated gene turned out to be related to interferon signaling.”

The researchers are now enrolling patients in a clinical trial to test JAK inhibitors in patients with SAVI and other rare autoinflammatory syndromes for which there are no satisfactory treatments.