Insights from two recent studies suggest novel avenues for treating the autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The NIH’s National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) supported the pair of studies that sought to better understand why the immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues and organs, as happens in SLE. The work could possibly impact other autoimmune diseases as well.

SLE is a chronic, inflammatory illness, that most often strikes women of childbearing age, though men and children also may be affected. The symptoms vary but the most common are sore, swollen joints, muscle aches and fatigue. Over time, the disease can damage the body’s organs and cause serious problems like kidney or cardiovascular disease. SLE has no cure, but non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines, steroids and other immune suppressants help control the symptoms. Many research efforts aim to understand how the immune system goes awry in SLE, with the goal of uncovering better ways to treat it.

Betty Diamond, M.D., of the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, led one such effort that produced results in Nature Immunology. Dr. Diamond’s group, intrigued by an earlier finding that a variation in a gene called PRDM1 increases a person’s risk of developing SLE, delved into the gene’s role in the immune system. Building on this work, Diamond’s team showed that female mice—but not males—engineered to lack PRDM1 in dendritic cells, a type of immune cell, showed signs of autoimmunity problems similar to those in people with SLE.

Additional experiments showed that loss of PRDM1 in dendritic cells leads to a rise in an enzyme, cathepsin S, which breaks up proteins in preparation for the fragments’ display on the cell surface. This processing step is an essential part of the T cell-mediated arm of the immune response, an important contributor to autoimmunity. When the researchers treated the engineered mice with a cathepsin S inhibitor, the lupus-like features abated in the female mice. While further research is needed, this finding suggests that cathepsin S represents a novel therapeutic target for SLE.

“What we’d like to be able to do is to intervene early in lupus, before any tissue damage occurs,” said Dr. Diamond. “By studying SLE risk genes, we hope to gain a better understanding of the immune system changes that set the stage for the disease and ultimately to find ways to stymie it before it truly sets in.”

The second study, published in the Journal of Immunology and led by Vasileios Kyttaris, M.D., of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, focused on an inflammatory molecule called IL-23. His group noticed that this molecule is elevated in the blood of SLE patients, suggesting a role in the disease. To investigate this possibility, the researchers tested the effect of IL-23 on cultured T cells taken from SLE patients. They found that exposure to IL-23 led to the expansion of the troublesome T cell subtypes associated with SLE.

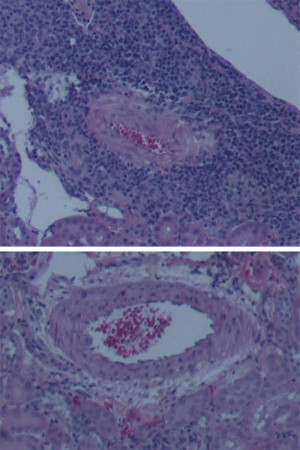

Probing further, they next tested IL-23’s effects in a mouse model of SLE. These mice, called MLR.lpr mice, spontaneously exhibit signs of lupus, including high levels of T cell subtypes associated with the disease and acute kidney damage. To see if IL-23 plays a part in the mice’s SLE-like symptoms, they engineered a strain of MLR.lpr mice that is insensitive to IL-23’s effects. They observed lower levels of SLE-associated T cell subtypes and inflammatory molecules in these mice, as well as reduced severity of kidney damage, compared to IL-23-sensitive MLR.lpr mice.

These findings revealed that IL-23 likely plays an important role in SLE, and showed that in mice, blocking the molecule’s effects diminishes signs of the disease. Additional research will reveal if the same is true in humans.

“Lupus, a disease that affects more than a million Americans, is treated with non-specific medicines that can have troubling side effects,” said Dr. Kyttaris. “The discovery that we can prevent disease development, especially kidney damage, in lupus-prone animals by targeting IL-23 offers the possibility of a new, more targeted approach toward treatment.”

Dr. Diamond’s study was supported by NIAMS (R01-AR065209), the Lupus Research Alliance and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency.

Dr. Kyttaris’s study was supported by NIAMS (R01-AR060849) and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01-AI085567).

###

Increased Cathepsin S in Prdm1-/- Dendritic Cells Alters the TFH Cell Repertoire and Contributes to Lupus. Kim SJ, Schätzle S, Ahmed SS, Haap W, Jang SH, Gregersen PK, Georgiou G, Diamond B. Nat Immunol. 2017 Jul 10. doi: 10.1038/ni.3793. PMID: 28692065

IL-23 Limits the Production of IL-2 and Promotes Autoimmunity in Lupus. Dai H, He F, Tsokos GC, Kyttaris VC. J Immunol. 2017 Aug 1;199(3):903-910. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700418. Epub 2017 Jun 23. PMID: 28646040